Some time ago, I needed to load balance websocket connections over AWS Elastic Load Balancers (ELB) or Classic Load Balancers as they are now called. But ELBs did not (and still don’t) support proxying websocket traffic over their HTTP(S) listener. To support websocket traffic, a TCP listener is required. This means that the proxy server (ELB) looses knowledge of the HTTP protocol since it goes from being a layer 7 (application) proxy to being a layer 4 (transport) proxy. Without knowledge of HTTP, the proxy can’t add the X-Forwarded-For HTTP header to let upstream servers know what the original client IP address is.

This problem is exactly what the PROXY protocol has been created to solve. It allows “Application Protocol” agnostic proxies (or “dumb proxies” like its specification calls them) to inject data about the calling client in the request being proxied without knowing about the proxied protocol by staying efficient.

Let’s look at how this PROXY protocol works.

Why do we need the PROXY protocol?

First, let’s go through the PROXY protocol specification. It was created by HAProxy in 2010 and since then as gone through 6 different updates. The last update to the specification was introduced in 2017. It has evolved since its creation into two versions which I explain in more details later.

The abstract of the protocol does a good job of explaining the why of it:

The PROXY protocol provides a convenient way to safely transport connection information such as a client’s address across multiple layers of NAT or TCP proxies. It is designed to require little changes to existing components and to limit the performance impact caused by the processing of the transported information.

To explain it in my own words. The goal of the PROXY protocol is to allow TCP “dumb proxies”, proxies operating at the transport layer (layer 4 of the OSI model), to inject data about the original source and destination addresses to their upstream servers without knowledge of the underlying protocol. The PROXY protocol is designed to support any application layer protocol like FTP, SMTP, IMAP, MySQL Protocol, and other protocols built on top of TCP or UDP. As can be seen with this extensive list of protocols, it enables a given proxy implementing adding the PROXY protocol header to a request to expose data on the original client without knowing anything about the protocol being proxied and therefore being more lightweight and not having to evolve to follow additions to higher level protocols like having to know about X-Forwarded-For and its replacement the Forwarded header for HTTP.

Version 1 Specification

The version 1 of the protocol is text based. It is human readable and therefore faciliates adoption and implementations.

Here is a text representation of an HTTP request containing the PROXY protocol version 1 header:

PROXY TCP4 192.168.0.1 192.168.0.11 56324 443\r\n

GET / HTTP/1.1\r\n

Host: 192.168.0.11\r\n

\r\n

All version 1 fields are separated by exactly one space " " (\x20):

- Signature

- Constant 5 bytes identifying the first line of a request as being a version 1 PROXY protocol line.

- Position: 0

- Value:

PROXY->\x50 \x52 \x4F \x58 \x59 - INET Protocol

- Proxied protocol and family. Only TCP and TCP6 allowed.

- Source Address

- IPv4 for TCP or IPv6 for TCP6.

- Destination Address

- IPv4 for TCP or IPv6 for TCP6.

- Source Port

- Number between 0..65535

- Destination Port

- Number between 0..65535

Version 2 Specification

The version 2 of the protocol is binary based which means that bits and bytes positioning are defined as part of the protocol.

The Cloudflare PROXY protocol documentation does a very good job of explaining the protocol. Specifically, it provides a protocol header diagram giving a very good high level view of the binary representation of the PROXY protocol version 2:

0 1 2 3

Bits 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| |

+ +

| Proxy Protocol v2 Signature |

+ +

| |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

|Version|Command| AF | Proto.| Address Length |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| IPv4 Source Address |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| IPv4 Destination Address |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Source Port | Destination Port |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

|<--------------------- 32 bits ---------------------->|

| Byte | Byte | Byte | Byte |

(This diagram and explanation only refers to TCP + IPv4. Other representations exist for UDP, IPv6 and UNIX sockets.)

Reading this diagram:

- Every tick represents a one bit position

- Every line contains 32 bits or 4 bytes (8 * 4)

Here is an hexadecimal representation of an HTTP request containing the PROXY protocol version 2 header:

0d 0a 0d 0a 00 0d 0a 51 55 49 54 0a 21 11 00 0c |.......QUIT.!...|

ac 13 00 01 ac 13 00 03 a6 52 00 50 47 45 54 20 |.........R.PGET |

2f 20 48 54 54 50 2f 31 2e 31 0d 0a 48 6f 73 74 |/ HTTP/1.1..Host|

3a 20 6c 6f 63 61 6c 68 6f 73 74 3a 38 30 38 30 |: localhost:8080|

0d 0a 0d 0a |....|

<--------------- Bytes ----------------> <---- ASCII ---->

The fields of version one are defined with a position and bit representation:

- Signature

- Constant 12 bytes allow an proxy to identify that the request starts with a PROXY protocol header.

- Length: 3 * 32 bits = 12 bytes

- Position: bytes 0 to 11

- Value:

\x0D \x0A \x0D \x0A \x00 \x0D \x0A \x51 \x55 \x49 \x54 \x0A - Version

- Constant 4 bits that must always be equal to

\x2version 2. Only uses the 4 highest bits of the 13th byte. The other 4 bits are used by the command field. - Length: 4 bits.

- Position: Highest 4 bits of the 13th byte.

- Value:

\x2(binary:0010) - Command

- Indicates whether the request was proxied or not. It is useful to know if the addresses should be ignored or not.

- Length: 4 bits.

- Position: Lowest 4 bits of the 13th byte.

- Value:

\x0(binary:0000):LOCAL: request is not from a proxy.\x1(binary:0001):PROXY: request is from a proxy.

- Address Family

- Original Address Family of the socket used to connect to the proxy.

- Length: 4 bits.

- Position: Highest 4 bits of the 14th byte.

- Value:

\x0(binary:0000):AF_UNSET: Used for theLOCALcommand.\x1(binary:0001):AF_INET: IPv4\x2(binary:0010):AF_INET6: IPv6\x3(binary:0011):AF_UNIX: UNIX

- Transport Protocol

- The protocol used to connect to the proxy. With the Address Family, we can infer the addresses types and length.

AF_INET+STREAM: TCP over IPv4AF_INET+DGRAM: UDP over IPv4AF_INET6+STREAM: UDP over IPv4AF_INET6+DGRAM: UDP over IPv6AF_UNIX+STREAM: UNIX streamAF_UNIX+DGRAM: UNIX datagram

- Length: 4 bits.

- Position: Lowest 4 bits of the 14th byte.

- Value:

\x0(binary:0000):AF_UNSET: Used for theLOCALcommand.\x1(binary:0001):STREAM: TCP\x2(binary:0010):DGRAM: Datagram (UDP or SOCK_DGRAM)

- Address Length

- The length of the address fields (source, destination) addresses and port. In Network Order (Big Endian), which means the most significant byte is at the lowest address. The length of the address + the number of bytes before the address is the total length of the header.

- Length: 2 * 8 bits = 2 bytes.

- Position: 15th and 16th bytes.

- Source Address

- The source address of the request. Each byte represent an integer from 0 to 255.

- Length: 4 bytes (IPv4)

- Position: 17th to 20th bytes (IPv4)

- Destination Address

- The destination address of the request. Each byte represent an integer from 0 to 255.

- Length: 4 bytes (IPv4)

- Position: 21th to 24th bytes (IPv4)

- Source Port

- The source port of the request. The bytes are in Network Order (Big Endian). Which means the most significant byte is at the lowest address.

- Length: 2 bytes (IPv4)

- Position: 25th and 26th bytes (IPv4)

- Destination Port

- The destination port of the request. The bytes are in Network Order (Big Endian). Which means the most significant byte is at the lowest address.

- Length: 2 bytes (IPv4)

- Position: 27th and 28th bytes (IPv4)

Security Considerations

The PROXY protocol specification raises important security considerations. Here are the main concerns. Please consult the specification for the full list.

- Receivers MUST only accept the PROXY protocol if configured to do so.

- Receivers MUST only accept the PROXY protocol header from a trusted downstream proxies.

- Receivers MUST not try to guess whether the PROXY protocol header is present or not.

These considerations are there to make sure that a downstream client cannot inject a PROXY protocol header without the receiver trusting the downstream client. Not enforcing this would allow any client to override the client IP and obfuscate itself.

Deep Dive

Now that we covered the specification, let’s try to experiment with the concept. It would be useful to test current implementations of the protocol and have a look at the version 1 and 2 header that gets written on a TCP stream.

To setup a testing environment, I used docker-compose to quickly have a networking environment and various components. To test the protocol we need these components:

- nginx-edge: a TCP proxy configured to add the PROXY protocol version 1 header to proxied requests.

- haproxy-edge: a TCP proxy configured to add the PROXY protocol version 2 header to proxied requests.

- nginx-proxy: an HTTP proxy configured to read incoming PROXY protocol version 1 and 2 headers and to add the X-Forwarded-For header to proxied requests.

- netcat: a TCP server printing the TCP request. Also used to print in hexadecimal format to inspect version 2 requests.

Here are all the components together:

PROXY protocol version 1

> curl -v http://localhost/

netcat_1 | PROXY TCP4 172.19.0.1 172.19.0.3 42272 80

netcat_1 | GET / HTTP/1.1

netcat_1 | Host: localhost:8080

netcat_1 | User-Agent: curl/7.68.0

netcat_1 | Accept: */*

PROXY protocol version 1 or 2 to Application

> curl -v http://localhost/

netcat_1 | GET / HTTP/1.0

netcat_1 | Host: localhost

netcat_1 | X-Real-IP: 172.19.0.1

netcat_1 | X-Forwarded-For: 172.19.0.1

netcat_1 | Connection: close

netcat_1 | User-Agent: curl/7.68.0

netcat_1 | Accept: */*

PROXY protocol version 2

> curl -v http://localhost/

netcat_1 | 00000000 0d 0a 0d 0a 00 0d 0a 51 55 49 54 0a 21 11 00 0c |.......QUIT.!...|

netcat_1 | 00000010 ac 13 00 01 ac 13 00 03 a6 52 00 50 47 45 54 20 |.........R.PGET |

netcat_1 | 00000020 2f 20 48 54 54 50 2f 31 2e 31 0d 0a 48 6f 73 74 |/ HTTP/1.1..Host|

netcat_1 | 00000030 3a 20 6c 6f 63 61 6c 68 6f 73 74 3a 38 30 38 30 |: localhost:8080|

netcat_1 | 00000040 0d 0a 55 73 65 72 2d 41 67 65 6e 74 3a 20 63 75 |..User-Agent: cu|

netcat_1 | 00000050 72 6c 2f 37 2e 36 38 2e 30 0d 0a 41 63 63 65 70 |rl/7.68.0..Accep|

netcat_1 | 00000060 74 3a 20 2a 2f 2a 0d 0a 0d 0a |t: */*....|

netcat_1 | 0000006a

Two hops TCP proxies resulting in two PROXY protocol header

Notice the two PROXY protocol headers prepended to the request. First a version 1 and then a version 2.

netcat_1 | 00000000 0d 0a 0d 0a 00 0d 0a 51 55 49 54 0a 21 11 00 0c |.......QUIT.!...|

netcat_1 | 00000010 ac 14 00 06 ac 14 00 03 cb 50 00 50 50 52 4f 58 |.........P.PPROX|

netcat_1 | 00000020 59 20 54 43 50 34 20 31 37 32 2e 32 30 2e 30 2e |Y TCP4 172.20.0.|

netcat_1 | 00000030 31 20 31 37 32 2e 32 30 2e 30 2e 36 20 34 30 36 |1 172.20.0.6 406|

netcat_1 | 00000040 33 34 20 38 30 0d 0a 47 45 54 20 2f 20 48 54 54 |34 80..GET / HTT|

netcat_1 | 00000050 50 2f 31 2e 31 0d 0a 48 6f 73 74 3a 20 31 32 37 |P/1.1..Host: 127|

netcat_1 | 00000060 2e 30 2e 30 2e 31 3a 38 30 38 32 0d 0a 55 73 65 |.0.0.1:8082..Use|

netcat_1 | 00000070 72 2d 41 67 65 6e 74 3a 20 63 75 72 6c 2f 37 2e |r-Agent: curl/7.|

netcat_1 | 00000080 36 38 2e 30 0d 0a 41 63 63 65 70 74 3a 20 2a 2f |68.0..Accept: */|

netcat_1 | 00000090 2a 0d 0a 0d 0a |*....|

netcat_1 | 00000095

Implementing a PROXY protocol parser

After reading the specification and experimenting a little with some proxies, I started to have a pretty good mental model of the PROXY protocol and how it integrated with TCP.

One thing I had more trouble with is how to parse the header and use the data it contained. Here is how I did it for each protocol version.

Parsing Version 1

package version1

import (

"bufio"

"bytes"

"fmt"

)

// ProxyInfo represents the PROXY protocol information.

type ProxyInfo struct {

Version string

AddrFamily string

SrcAddr string

SrcPort string

DstAddr string

DstPort string

}

// MaybeParseVersion1 returns information about the proxy header if contained in

// the buffered reader of an incoming request.

//

// No bytes are read from the buffered reader if there is no PROXY protocol header

// prepended to the request.

//

// If a PROXY protocol header is found, only the bytes of the PROXY protocol

// are consumed from the reader to allow the rest of the bytes to be used for

// a layer 7 protocol for example HTTP.

func MaybeParseVersion1(bufReader *bufio.Reader) (*ProxyInfo, error) {

// Only peek at 5 bytes to check if it starts with PROXY

sigBytes, err := bufReader.Peek(5)

if err != nil {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("peek error: %w", err)

}

// Is the request data starting with `PROXY`?

isV1 := len(sigBytes) >= 5 && bytes.Equal(sigBytes[:5], []byte("PROXY"))

if !isV1 {

return nil, nil

}

// read until CRLF \r\n

line, isPrefix, err := bufReader.ReadLine()

if err != nil {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("version 1 readLine error: %w", err)

}

if isPrefix {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("version 1 line too long")

}

// split fields by space

sections := bytes.Split(line, []byte("\x20"))

if len(sections) != 6 {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("version 1 header corrupted, not enough sections (got: %d, want: %d)", len(sections), 6)

}

return &ProxyInfo{

Version: "1",

AddrType: string(sections[1]),

SrcAddr: string(sections[2]),

DstAddr: string(sections[3]),

SrcPort: string(sections[4]),

DstPort: string(sections[5]),

}, nil

}

Parsing Version 2

package version2

import (

"bufio"

"bytes"

"encoding/binary"

"errors"

"fmt"

"io"

"net"

"strconv"

)

// protocolV2HeaderLen represents the number of bytes needed

// to start parsing the protocol v2 header.

const protocolV2HeaderLen = 16

// protocolV2SignatureBytes represents the 12 constant bytes of the v2 signature.

var protocolV2SignatureBytes = []byte("\x0D\x0A\x0D\x0A\x00\x0D\x0A\x51\x55\x49\x54\x0A")

// ProxyInfo represents the PROXY protocol information.

type ProxyInfo struct {

Version string

Command string

AddrFamily string

TransportProtocol string

SrcAddr string

SrcPort string

DstAddr string

DstPort string

}

// MaybeParseVersion2 returns information about the proxy header if contained into

// the buffered reader of an incoming request.

//

// No bytes are read from the buffered reader if there is no PROXY protocol header

// prepended to the request.

//

// If a PROXY protocol header is found, only the bytes of the PROXY protocol

// are consumed from the reader to allow the rest of the bytes to be used for

// a layer 7 protocol for example HTTP.

func MaybeParseVersion2(bufReader *bufio.Reader) (*ProxyInfo, error) {

// Peek at enough bytes to be able to know if the protocol is a version 2

// and to get the length of the PROXY protocol header.

sigBytes, err := bufReader.Peek(protocolV2HeaderLen)

if err != nil {

return nil, fmt.Errorf("peek error: %w", err)

}

// Check if the peeked bytes start with a version 2 signature.

isV2 := len(sigBytes) >= protocolV2HeaderLen && bytes.Equal(sigBytes[:len(protocolV2SignatureBytes)], protocolV2SignatureBytes)

if !isV2 {

return nil, nil

}

// sigBytes[12] contains the version

// Check if the version == 2

if sigBytes[12]>>4 != 0x2 {

return nil, errors.New("unknown version of protocol")

}

// sigBytes[14:16] contains the length of the addresses

// Integer are sent over the wire using network byte order.

// To use them as integer we need to translate them into

// a go primitive.

lenInt := binary.BigEndian.Uint16(sigBytes[14:16])

// The total header length is the length of the address plus the

// constant length of 16 (signature + version + bytes for length)

hdrLenInt := 16 + lenInt

// Consume bytes from the request since we now know the request contains a

// version 2 header and we have the length of the header.

line := make([]byte, hdrLenInt)

_, err = io.ReadFull(bufReader, line)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

p := &ProxyInfo{

Version: "2",

}

// line[12] contains the command

// Parse lower bits of 13th byte

// AND 4 higher bits with zero (making them zero)

c := line[12] & 0x01

switch c {

case 0x0:

p.Command = "LOCAL"

case 0x1:

p.Command = "PROXY"

default:

return nil, errors.New("unknown version 2 command")

}

// line[13] contains the address family and the transport protocol.

// Parse higher bits of 14th byte for the address family.

// From 11110000 to 00001111 where the 4 first bits

// are shifted to the right.

af := line[13] >> 4

switch af {

case 0x0:

p.AddrFamily = "AF_UNSPEC"

case 0x1:

p.AddrFamily = "AF_INET"

case 0x2:

p.AddrFamily = "AF_INET6"

case 0x3:

p.AddrFamily = "AF_UNIX"

default:

return nil, errors.New("unknown version 2 Address Family")

}

// Parse lower bits of 14th byte for the transport protocol.

// AND 4 higher bits with zero (making them zero)

tp := line[13] & 0x01

switch tp {

case 0x0:

p.TransportProtocol = "UNSPEC"

case 0x1:

p.TransportProtocol = "STREAM"

case 0x2:

p.TransportProtocol = "DGRAM"

default:

return nil, errors.New("unknown version 2 Transport Protocol")

}

// Infer the Address and Port types by using the combination of

// Address Family and Transport Protocol.

switch line[13] {

case 0x00:

p.SrcAddr = "UNSPEC"

p.SrcPort = "UNSPEC"

p.DstAddr = "UNSPEC"

p.DstPort = "UNSPEC"

case 0x11: // TCP + IPv4

p.SrcAddr = net.IP(line[16:20]).String()

p.DstAddr = net.IP(line[20:24]).String()

// Translate network byte order integer into a go primitive.

p.SrcPort = strconv.FormatUint(uint64(binary.BigEndian.Uint16(line[24:26])), 10)

p.DstPort = strconv.FormatUint(uint64(binary.BigEndian.Uint16(line[26:28])), 10)

case 0x21: // TCP + IPv6

p.SrcAddr = net.IP(line[16:32]).String()

p.DstAddr = net.IP(line[32:48]).String()

// Translate network byte order integer into a go primitive.

p.SrcPort = strconv.FormatUint(uint64(binary.BigEndian.Uint16(line[48:50])), 10)

p.DstPort = strconv.FormatUint(uint64(binary.BigEndian.Uint16(line[50:52])), 10)

default:

return nil, errors.New("unknown version 2 Address Type and Transport Protocol combination")

}

return p, nil

}

Real-life Usage

After looking at how PROXY protocol works and how it can be implemented. Let’s look at some Cloud providers to see where the protocol is used. To do so, here is a list of Load Balancers for each providers with the mechanism used to preserve the Client Address.

Azure

- Front Door Service is a layer 7 proxy that supports injecting the X-Forwarded-For header

- Application Gateway is a layer 7 proxy that supports injecting the X-Forwarded-For header

- Azure Load Balancer is a Network Load Balancer that preserves the Client IP by only being a pass-through Load Balancer.

Google Cloud Platform

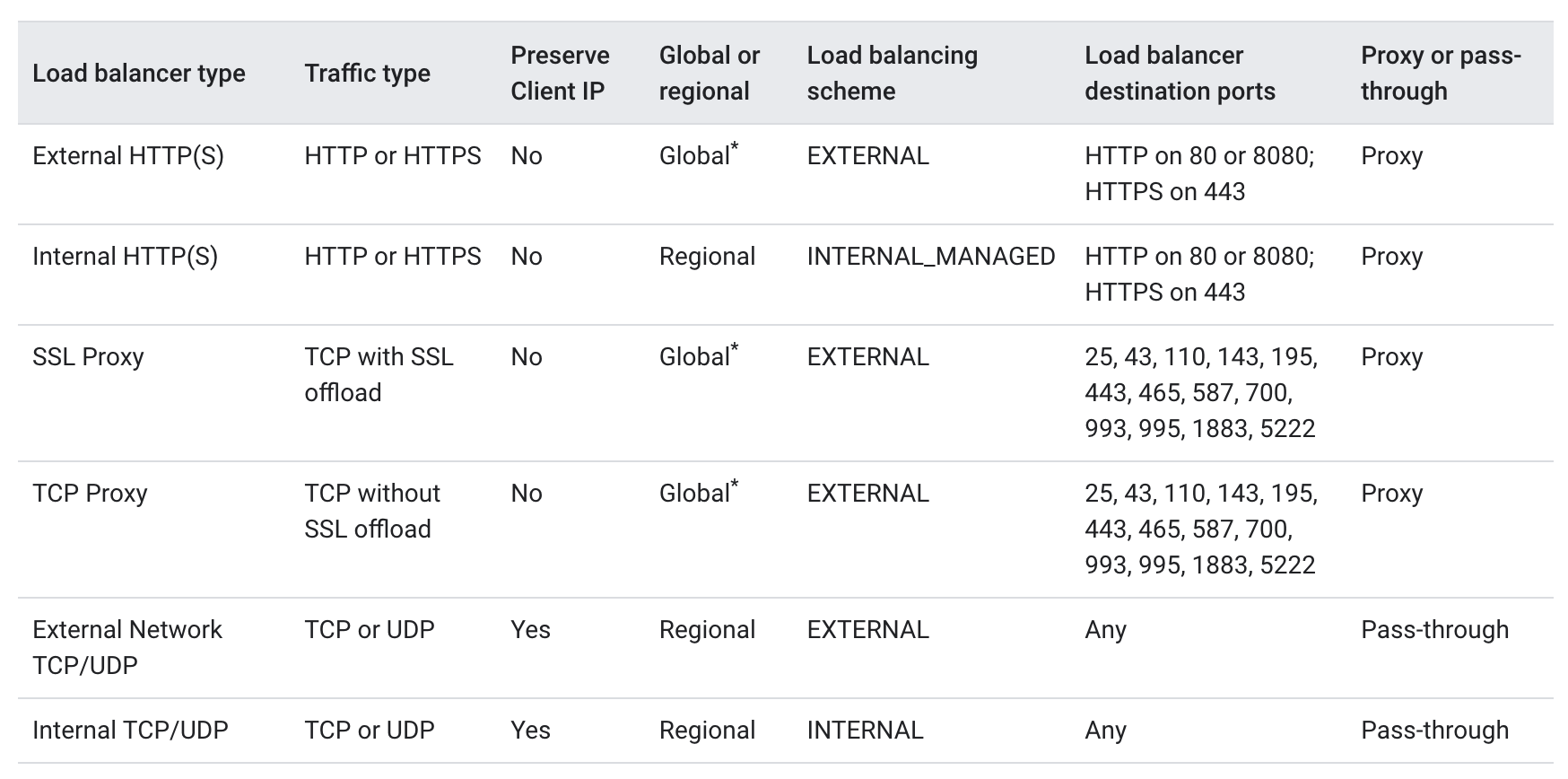

The six different Load Balancers are summarized by Google with one of the feature covered being Preserve Client IP:

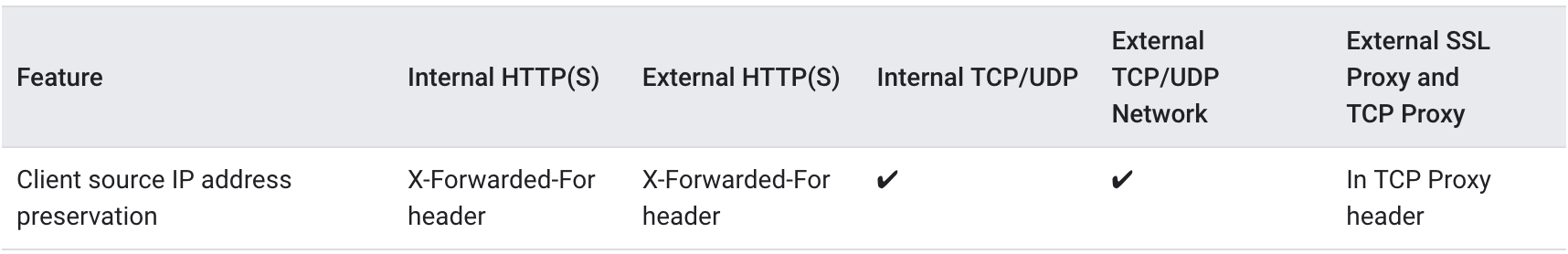

Google also has more detailed comparison going as far as explaining how preservation of client IP can be done with the various Load Balancers:

The TCP Proxy Header referred to in this table refers to the PROXY protocol. Therefore, TCP and SSL Proxies support the PROXY protocol.

Amazon Web Services

- Classic Load Balancer (previously named ELB/Elastic Load Balancer) supports the PROXY protocol version 1 for TCP listeners. It also supports

X-Forwarded-Forfor HTTP listeners. - Network Load Balancer preserves the source address and port without the

X-Forwarded-Forheader or the PROXY protocol when targets are identified by instance ID. When targets are identified by IP address, the source address is not preserved. To work around this limitation, the Network Load Balancer supports the PROXY protocol version 2. - Application Load Balancers (ALB) automatically forward the X-Forwarded-For header to their targets.

Cloudflare

Cloudflare supports injecting both a X-Forwarded-For header and also the PROXY protocol header.

DigitalOcean

The DigitalOcean Load Balancer has support for the PROXY protocol version. It also supports the X-Forwarded-For header when proxying HTTP.

Linode

The Linode NodeBalancer has support for the X-Forwarded-For header. PROXY protocol support is planned for 2020.

Rackspace

The Rackspace Cloud Load Balancer has support for the X-Forwarded-For header. It does not support PROXY protocol.

Alternatives

The PROXY protocol exists to ensure that the client IP / source address of the original request is preserved across hops to upstream servers. We’ve covered a lot on the PROXY protocol. But as seen by the approaches taken by Cloud Providers, there are other approaches than using some sort of layer 4 or 7 proxy to perform load balancing. These approaches are very interesting and promising. They make the PROXY protocol less and less needed.

The Kubernetes proxy, Kube-Proxy, has different interesting approaches to proxying while preserving the Client IP. It can work in 3 modes: userspace, iptables, and IPVS. The userspace mode requires the proxy to do the TCP handshake and therefore does not preserve the original Client IP. The iptable and IPVS modes both allow the kernel to perform the routing without reading the traffic and therefore both preserve the client IP without needing the PROXY protocol. The new IPVS approach also allow different load-balancing algorithm like lest conns, locality, weighted, …

There is also the big domain of Software Defined Networking that allows a service provider to configure switches to perform load-balancing by the network instead of by an application or proxy. This seems to be the approach taken by various Cloud Providers. Leveraging the network to perform the load balancing gets rid of single point of failures and increases performance. There can even be some advanced heuristics to improve load balancing algorithms like TCP performance, QoS, locality, least conns, …

There are also different tunneling/encapsulation protocol allowing incoming packets to be wrapped within another protocol and be delivered transparently as-is to the target application. One such protocol is the IP-in-IP tunneling protocol. IP-in-IP is supported natively by the Linux kernel and allows wrapping IP packets within another IP packet transparently.

Networking is a big world composed of so many different technologies. This list is just a tiny window in this wide world.

Conclusion

After taking a look at the PROXY protocol spec and after looking at how to implement it, I hope that I have been able to demystify it a little bit for you. Like almost everything we get to learn, it opens new doors and so many new questions. One thing is sure. Even though most of us will never have to create a PROXY protocol reader or writer, understanding the PROXY protocol makes us better at understanding trade-offs when choosing a Proxy or Load-Balancer for our applications.

The code snippets of this post are coming from a small project called Proxy Debugger. That project was created while writing this post. It is a server that outputs information about incoming requests like for example the Client IP, the X-Forwarded-For header, and the various PROXY Protocol header fields.