One of my core values is empathy. It is also one of the core principles where I work. You can feel the empathy in a lot of our day to day ceremonies, communication, documentation, code, code reviews, and even in our Pull Requests.

This post is about changing code by optimizing for happiness.

A few words on Empathy

Wikipedia defines empathy as being “the capacity to understand or feel what another person is experiencing from within their frame of reference, that is, the capacity to place oneself in another’s position”.

As part of being in a team, everyone will be faced with communicating with others. The way we express ourselves, the way we act, our non-verbal communication, the emojis we use, and our tone are examples of behaviours that impact people we interact with. Knowing how to keep this impact positive is important and can sometimes be difficult.

In a team, the behaviors of each member is important. It directly influences its culture. Having a team of empathic people allows the team to develop multiple facets of a highly productive team: trust, learning, cooperation, experimentations, embracing failures as a way to be better, reinventing themselves, self-managing, not afraid to show their vulnerability, … Empathy really enables individuals to do the best work of their careers.

But, empathy is the responsibility of every individual.

Start with why

One of the most important ways of changing code empathically is by explaining the why behind your change. When describing your change, think about how best to provide enough context to your reviewers. Taking a few minutes more to write some context pays off. It pays off because people care. Your team cares. They will try to understand why you are taking an approach over another one. They will try to understand where this change fits in the big picture of the feature you are working on. They won’t always know that what you are introducing is just the first iteration out of 10. By explaining the important aspects of your change, You can make them understand: what the plan is, what the next step is, and that it is not yet perfect but is just the first step towards making it perfect. We are all in this together. Sometimes, the only piece missing is setting up the context. With the same context and assumptions, we can all agree on the same direction to get to our destination.

What makes you the most confident to be able to review a pull request?

Figure 1: Title only

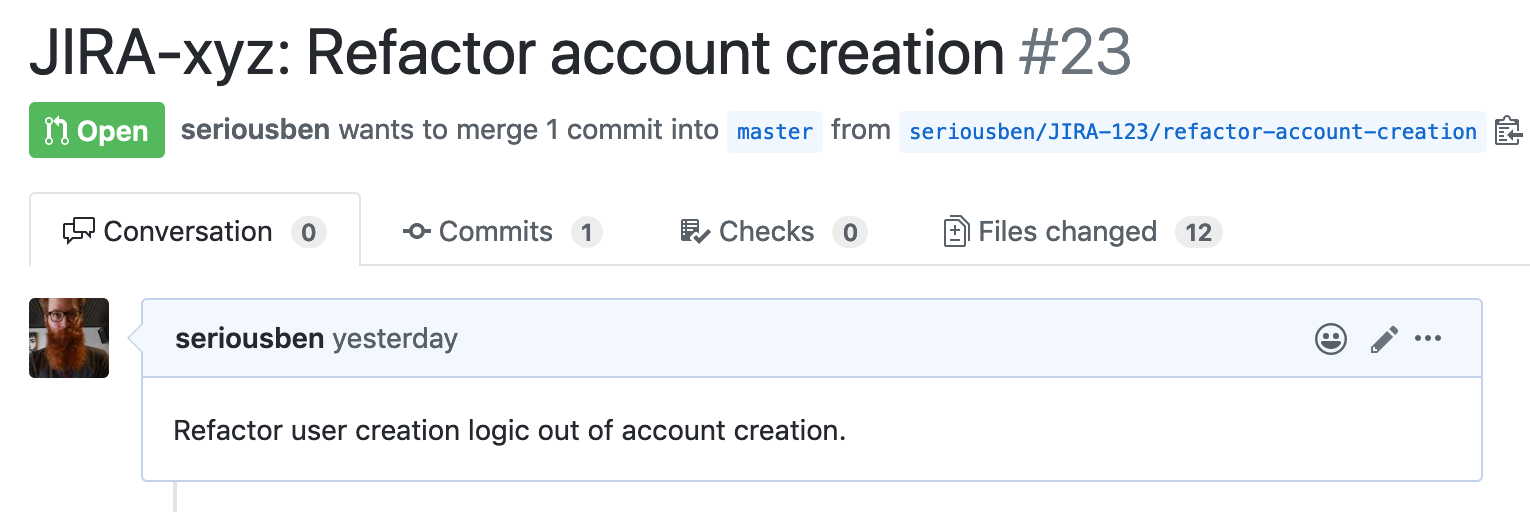

Figure 2: Description, but no why

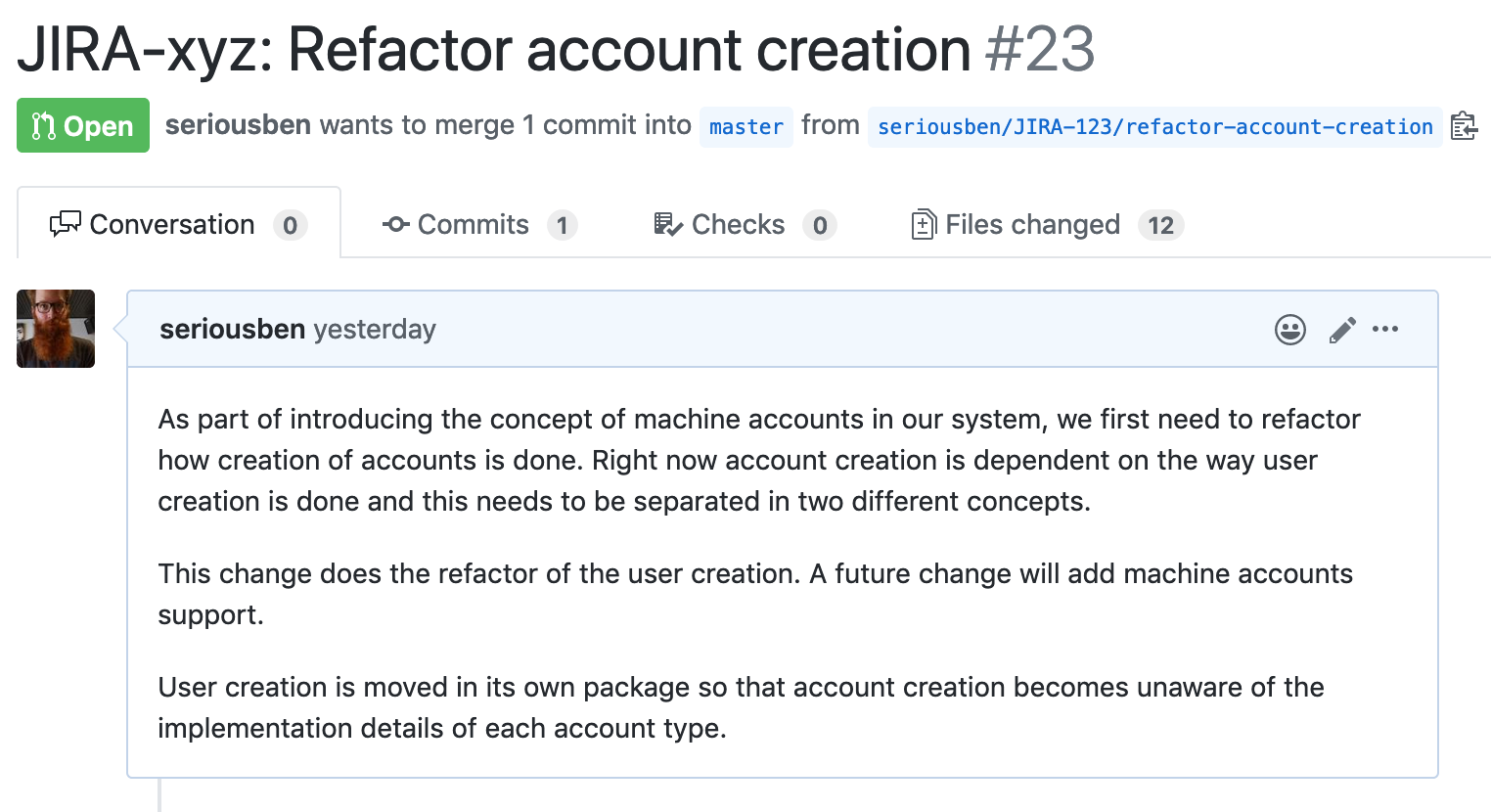

Figure 3: Description explaining the why

Having a little window into the author’s mind by having an explanation of why a given change is needed goes a long way. It always makes me feel great when the author has taken the time to explain the reasoning and the high level goal of what they did.

Another very interesting side-effect of explaining the why is that it sets expectations. It frames the code change within some specific constraint like time, quality, scope, and product management decisions. By giving facts, reviewers can focus on making sure the code does what it is supposed to do. Without that, some reviews can trigger big design or product decisions that slow down everyone. Writing information about the change means having those decisions taken beforehand which can be summarized very briefly in the Pull Request. In his paper “No Silver Bullet” , Fred Brooks says: “We still make syntax errors, to be sure; but they are fuzz compared to the conceptual errors in most systems”. This is very true. It is the reason why the best reviewers will spend their time focusing on whether a code change does what it is supposed to do by thinking about the system and business as a whole. Giving reviewers the context will help them provide much more value.

For remote teams, this is even more important. The more we can work asynchronously the more we save each other’s time and energy. It is also way more inclusive to people from different time zones that don’t always have the possibility of joining code review meetings to get the context of a change.

Commits as a powerful tool

A second tool we have in our toolbox to change code empathically is the structure of our change set. Commits. A lot of questions come to mind when thinking about commits. Are commits an implementation detail of a Pull Request? Should they only be useful to the author? Are they just a way to save in-progress work at the end of the day? Should they just be squashed when Pull Requests are merged? Those are just a few of those questions.

I have recently started to look at commits as a way to tell a story. Where every chapter of my story fits nicely within a commit. Each chapter is sized just perfectly to contain a meaningful change that readers (reviewers) can reason about. The chapters together form the story of my Pull Request.

Example: Commits of a Pull Request, What makes you the most happy?

Figure 4: One commit for lots of changes

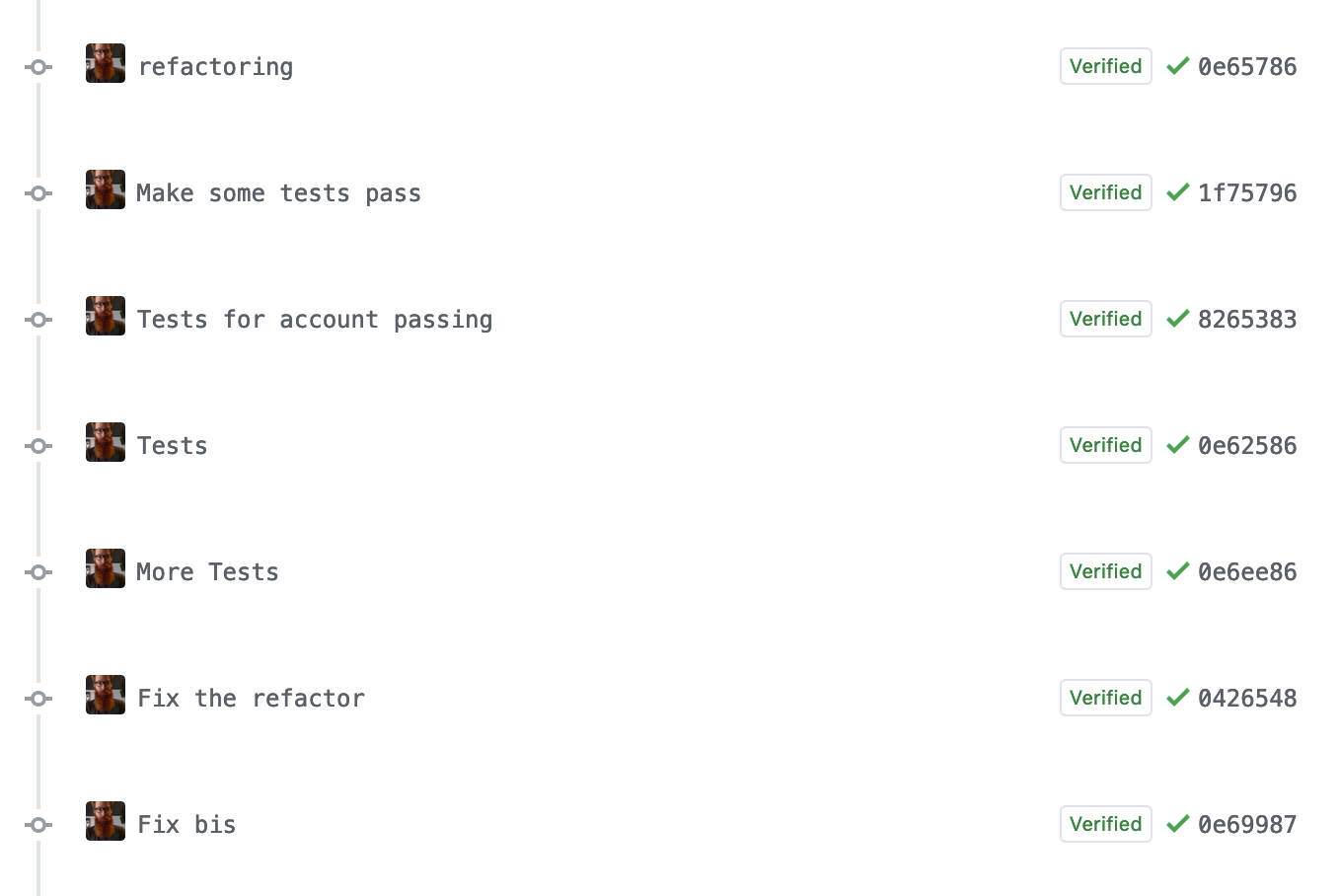

Figure 5: Multiple commits, but of no value to reviewers

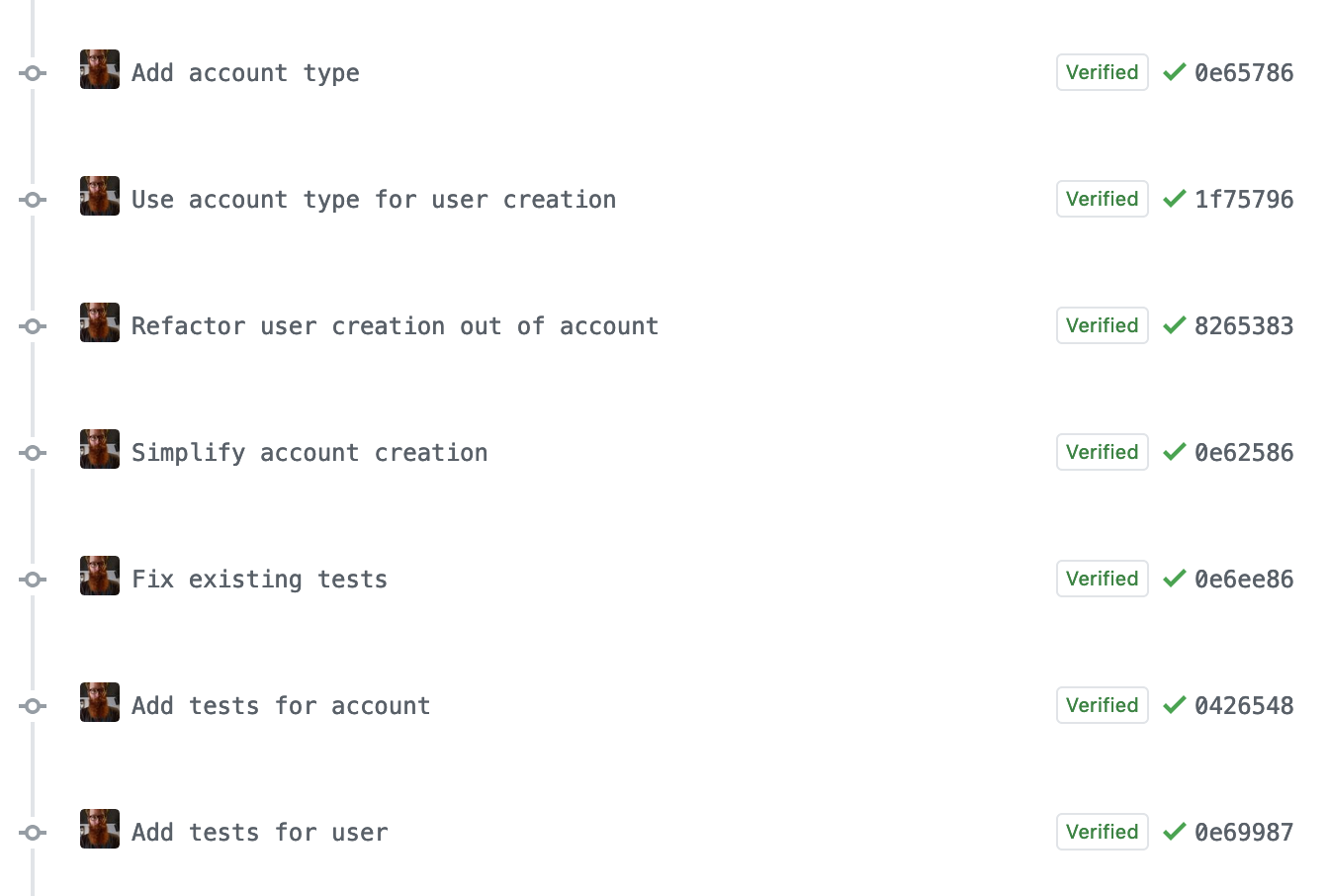

Figure 6: Multiple commits telling a story

The main reason behind telling a story by using commits is that having a nice narrative allows you to share some of your mental model with your reviewers. It splits your change into self-contained and self-reviewable units. It also empowers your reviewers to focus on specific changes that were introduced instead of letting them figure out what is important within big pull requests. It can be costly for reviewers to context switch from their task to reviewing somebody else’s code. Making it tougher to really figure out what is important in a timely way. Guiding them by splitting main work items in commits is a way to tell them that you value their opinion by structuring your changes.

On top of that, if I find myself telling more than one story, I often decide to publish them as two different books (pull requests). Splitting up such changes makes reviewers happy and also reduces the risk of changing unrelated pieces at once.

Don’t forget the code

Another important factor to change code empatically is the way you approach changing and writing it.

As part of writing code, I believe we should keep in a mind two key ideas: the “Principle of least astonishment” and the idea that “Code is read more often than written”. The Principle of least astonishment pushes us towards simple and comprehensible systems. Code that behaves in a surprising way is code that can be fragile and scary to change. Think about the next person that will change this code and make it easy to understand and modify the code you wrote.

The ideas that “Code is read more often than written” should impact the structure and documentation of your code. It also means that less code is not always better if it becomes tricky to understand and maintain. Optimizing code for read (not for IO read but for human reading code :) ) has the side effect of reducing the cognitive load required to understand a piece of code.

These two ideas are the foundation on which a lot of other recommendations come from.

Respect Conventions

Changing conventions in a Pull Request is probably not worth doing without having a discussion first. Conventions by their nature are typically subjects on which everyone has different opinions. It is typically a good idea for teams to rely on a style guide, linter, and formatter to enforce these conventions.

Conventions are important. They are one of the main factors for having a consistent system and code base. Consistency means that similar problems are solved in a similar way. Consistency reduces complexity by removing surprises a developer could find in the system. Conventions make reading code and changing code easier

Changing conventions is possible. But approach it with the understanding that you are not simply changing code but changing a process that each member of a team is following each day.

The Good Samaritan Rule

This rule goes like this: If you can improve something do it.

For example: fixing a typo, adding a missing comment, updating some old way of doing something to the new way, adding a missing log statement, …

If the improvement does not fit the story of your current Pull Request, create a Pull Request just for that change. It will be easily reviewed and people will even notice the extra care you spend improving the system.

Be friendly with the person that will come after you by making it easier for them.

Strategic Programming

The book “A philosophy of software design” by John Ousterhout defines the concept of strategic programming with these key ideas:

- Working code is not enough.

- Introducing unnecessary complexities to finish a task faster is not acceptable.

- The most important thing is the long-term structure of a system.

From these three axioms, it further develops the concept by saying that strategic programming requires an investment mindset. Investing slows you down a bit in the short term but speeds you up in the long term. Strategic programming is taking a little time to fix design issues instead of working around or patching them.

Putting this concept in practice allows for better code. But also for empathic code. By reducing the accidental complexity that often arises from an evolving system, it empowers programmers to ship business value faster over time. It reduces the size of the mental model required to change the system. It reduces the risk required to change a system that has become fragile because of complexity.

Do not be a “tactical tornado”, “the prolific programmer who pumps code faster than anyone”, “Often treated as heroes in some organizations [… but] leaving behind a wake of destruction [of workarounds, patches, local fixes for systemic issues, …]. The “tactical tornado” does not optimize for happiness but for short term gains that disrupts the system and the people.

Conclusion

I recognize that this article is pretty opinionated. But keep in mind that all the points discussed might or might not apply to you or your team. There are trade-offs to everything. But I am hoping that it can make yourself question how to be friendly, empathic, and inclusive to your coworkers.

A lot of this article is based on behaviors that my team has in our day to day work. A lot of the ideas and formulations of this article have been taken from the discussions and pull request reviews. This attention to other people’s feelings while tending towards excellence is why I am so proud to be part of this awesome team.

There are multiple areas that I did not talk about in this article. Being a good reviewer, Accepting critique of your code, Attributing code changes to the reviewers, … These could be different articles by themselves. But for now, make sure to always assume the best out of people!

Optimize for happiness!